Here is my latest guest appearance, with the talented poet and blogger Vatsarah Stavyah, in which I discuss being a writer as well as my novel Mystical Greenwood.

Many thanks to Vatsarah for this opportunity!

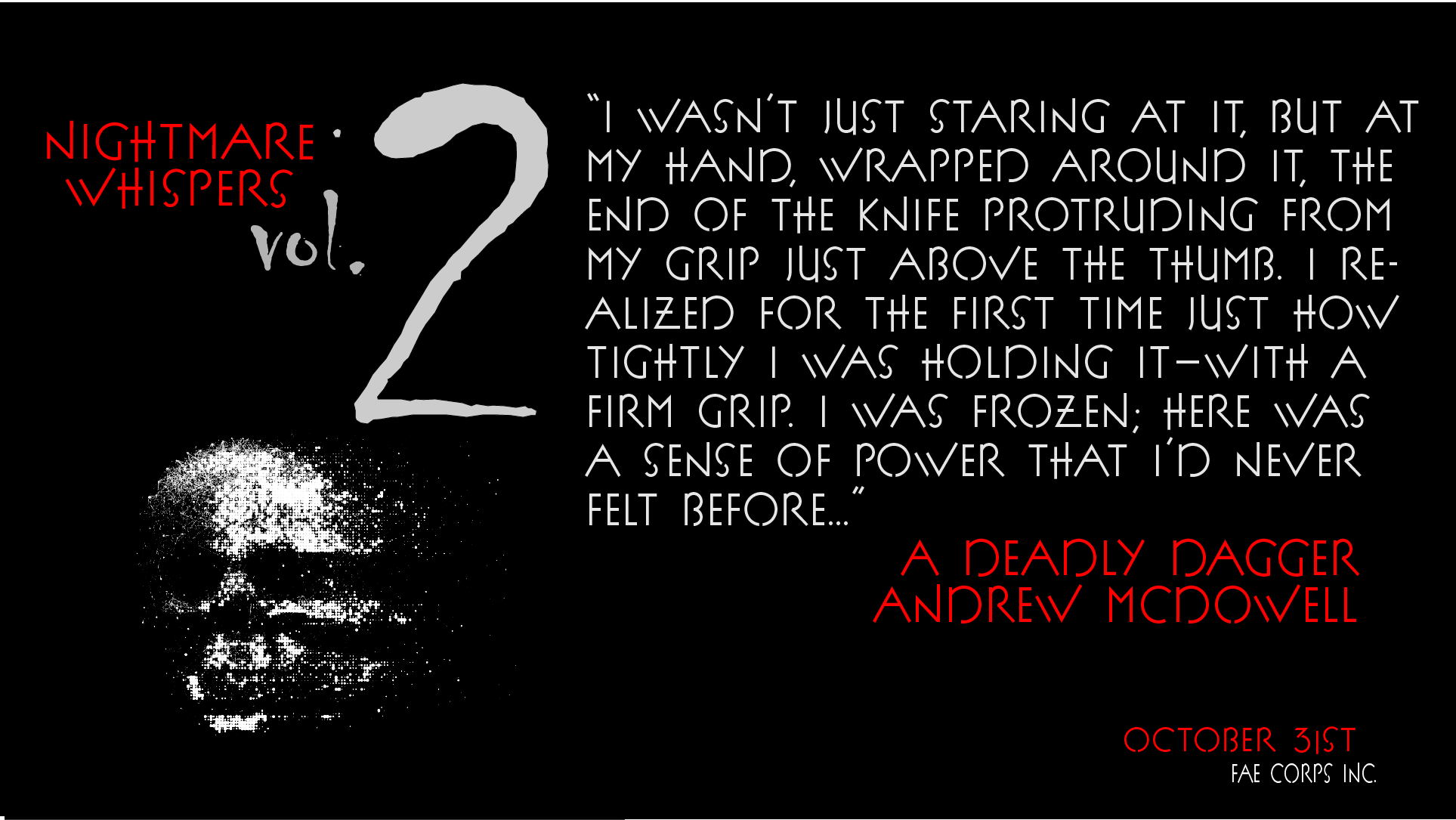

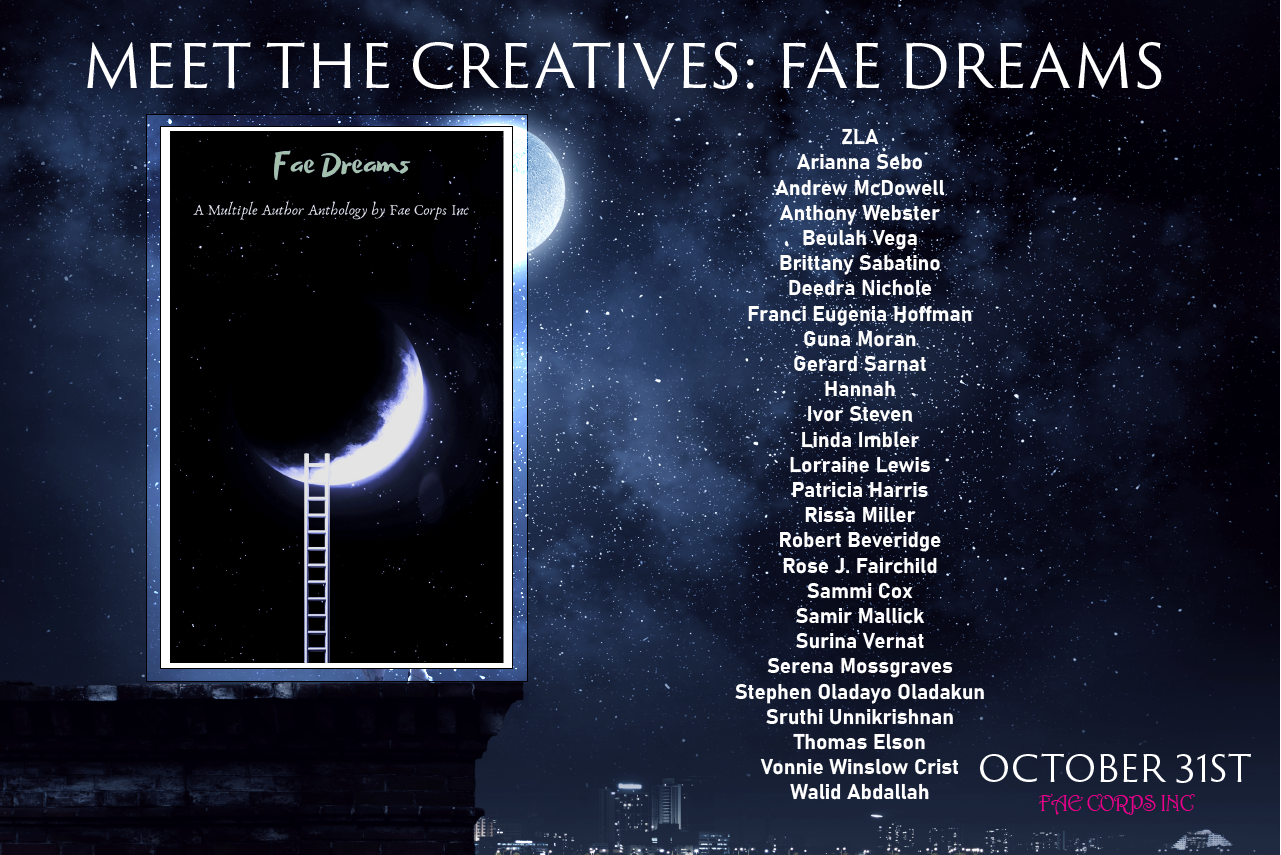

And for those of you haven’t seen or heard yet, I am going to have some short works appearing in two anthologies from Fae Corps Inc, Fae Dreams and Nightmare Whispers, Volume II, scheduled to be released on Halloween! Another poem will be appearing in another upcoming anthology from Indie Blu(e) Publishing titled As the World Burns. Be sure to keep an eye on my poetry and new short story page for future links!

Also, as today is 9/11, I ask for a moment of remembrance for those who died on this day 19 years ago, and for those who were affected by it.

The guest post is no longer available on the original site. Here is what the contents basically were:

When did you start writing?

I remember starting to write when I was 11. It was just little stories for the fun of it. I fantasized about writing more, but I didn’t truly get serious about it until I was 13.

How did your book ‘Mystical Greenwood’ happen?

I started out wanting to write a horror novel, and I was writing by hand because I hadn’t yet mastered keyboarding. That changed once I took a keyboarding class in my freshman year of high school. I also realized what I was writing was leaning more towards fantasy, so I just went with it. From there, it evolved into what it is now, taking on the theme of the importance of the natural world and wildlife.

What’s it about?

It’s about a teenage boy living in a remote village whose life changes when he encounters first a gryphon and then a mysterious healer. He and his brother eventually are forced to leave their home, and embark on a quest to find members of an ancient coven of sorcerers, because an evil sorcerer is bent on conquering the kingdom. In the process, as they discover something sacred and magical within every forest they cross through, they discover something more about themselves and their own role in this conflict.

Is this your debut novel? If not, how many books have you written?

It is the only novel I currently have out. All of my other current publications have been minor, mainly poetry (including in the anthology Faery Footprints, from Fae Corps Inc.) and one creative nonfiction essay about me having Asperger syndrome.

Before you start with a novel, do you in your mind have the plot and the characters you’re going to incorporate, or do you not know how the story is going to unfold unless you get done with it?

Do you have any favorite authors? If yes, please let me know who they are and why they inspire you.

I’m more of a pantser than a plotter, so the plot isn’t fully mapped out when I start. The little plotting that I do is minor, so I can work it out as I write. It’s hard to say that I have a favorite author when speaking of their work, because I’ve read a wide variety of works. But there are numerous authors whom I admire for their accomplishments, including William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Stephen King, Dan Brown, and Brad Meltzer to name a few.

When do you generally write? Do you follow a schedule, or do you write when you have an urge to pen down your thoughts?

Typically, it’s whenever I have an urge.

Where are you currently residing? Also, please let me know of your educational qualifications.

I live in Maryland, in the United States. I studied History and English at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, and Library & Information Science for grad school at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Was your becoming an author a conscious decision?

Once I got serious about writing, and poured dedication into it, there was no going back.

What are your hobbies and interests besides writing?

I’m something of a coin collector.

Tell me a bit about your works in progress. Do you plan on becoming a full-fledged author?

What would you like to tell the budding authors who lose motivation if a few of their works don’t do well?

My main work-in-progress right now is the sequel to Mystical Greenwood. I hope to continue the story with more conflict, some romance, and a focus on aquatic life. I know how I want it to end, but I need to connect the dots towards that end. I wish I could be a full-time author, but I know that is extremely unlikely. Only a select few are lucky enough to make it that way, so I can’t count on it nor expect it. My advice for budding authors is to not give up. Your first book may not always be the best, but you won’t know unless you keep going.

If there is something else that you wish to share, please do.

I am a member of the Maryland Writers’ Association and an associate nonfiction editor for the literary magazine JMWW.

Links:

Website

Facebook

YouTube

Goodreads