I’ve always been a fan of horror fiction, and every October I watch scary movies all month long. During my first semester at St. Mary’s College, I took a Freshman Seminar called Victorian Monsters and Modern Monstrosities. Professor Jennifer Cognard-Black introduced us (we came to be known as “Marvelous Monsters”) to six archetypes. With each we read a corresponding literary classic:

- Freak – Frankenstein

- Madwoman – Jane Eyre

- Schizo – The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

- Horrorscape – Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

- Deviant – Dracula

- Animagi – The Island of Dr. Moreau

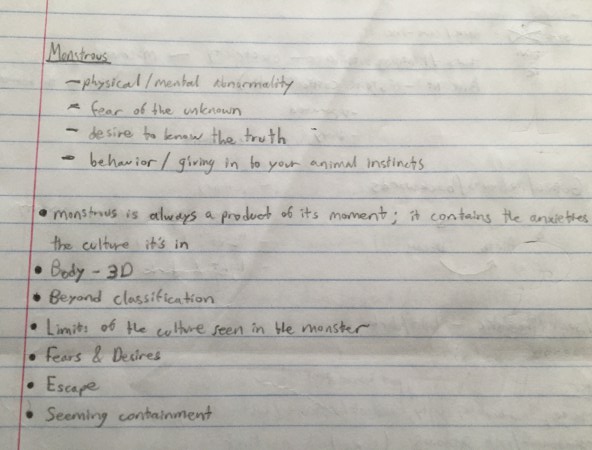

Here are some of my notes from the start of the seminar regarding core themes:

Indeed, these archetypes reflect Victorian social fears and limits. Yet there is something about what’s considered monstrous that draws people in. We delight in feeling terrified. We are interested in the unknown. During Victorian times revolutions were underway in science and philosophy. The establishment clashed with the Enlightenment.

The Freak is considered, as I wrote in my notebook, the “embodiment of cultural anxiety”. Freaks are the ultimate outsiders, who can never fit due to a social abnormality, physical or not. Dr. Frankenstein’s creation is a result of his desire to know higher truth. Yet, out of fear for what he achieved, he abandons his creation. The creature longs to be human. Born innocent, he teaches himself by observing them. Yet they ultimately reject him. Mary Shelley was shunned for being her eventual husband’s mistress while he was still married to his first wife. Shunned himself, Frankenstein’s creation becomes a raging and vengeful monster, but only because society made him one. He still has a heart and feels guilt.

The Deviant can infiltrate society and take it down from within, without guilt. Count Dracula moves to London and attacks young well-born women, who symbolize what is valued by Victorian society. After the character Lucy is vampirized, she attacks children, representative of society’s future. The vampire deviates from social norms through murder and raw sexuality (something Bram Stoker could only reference indirectly in his time), and operates secretively. Yet Dracula is from a different world than Victorian London. His is one of superstition, presenting a clash between Christian and non-Christian. Exotic landscapes and languages are seen as beautiful yet terrifying. Though Victorians saw themselves as cosmopolitan, they enjoyed expressing exotic tastes. Stoker merged old and new, drawing from folklore while using a contemporary setting.

Sometimes what is deviant to one culture is not to another. A Horrorscape can be seen as a Deviant story in reverse. After tumbling down the rabbit hole, Alice enters a world where everything that defined hers, her whole cultural upbringing, is turned upside down. Everyone’s mad. Alice tells the caterpillar she’s not herself. She cannot conform. She’s transgressive. Perhaps the inhabitants of Wonderland saw Alice as a Deviant trying to tear down their world.

The notion of giving in to one’s “animal” instincts is most clearly depicted in Animagi. They represent a move away from rational towards emotional, thus revealing the beast hidden within, which is violent and aggressive. Dr. Moreau’s creations blur the boundary between man and beast. Another famous example is the werewolf. Often those animals personifying evil are feared, exotic predators. Such instincts can be classified as Christian deadly sins: greed, gluttony, anger, and lust. Yet there is something appealing about giving in: a sense of freedom. H. G. Wells defied convention by advocating “free love,” and was notorious for his affairs.

The schizo is the ultimate human split between good and evil, yet it is often unclear which is the true personality. Though Jekyll’s desire to know the unknown results in a physical transformation (which is not required for schizos), it can exist solely within the mind), even if Hyde is guilty of crimes Jekyll would never commit, Hyde is still a part of him, and slowly takes over. It calls into question identity itself. Identity is in turn reflected in residency and possessions. Jekyll lives in a respectable, cosmopolitan neighborhood; Hyde’s is far less respectable. Once I watched a documentary discussing how Robert Louis Stevenson’s birthplace, Edinburgh, was a city divided between old and new, rich and poor, suggesting that duality may be what inspired his story.

Victorians had a dual perspective regarding women, at a time when many like Shelley’s mother began challenging the status quo and seeking rights in what was still a male-dominated world (a world in which Shelley published anonymously while Charlotte Brontë and her sisters used male pseudonyms). On one side was virginity, marriage and motherhood. On the other were Madwomen: temptresses, mistresses, witches – women who played upon men’s desires, using their femininity for selfish, nefarious purposes. The lunatic Bertha Mason prevents Jane Eyre from marrying Rochester because she’s his wife (though she would later be portrayed as a victim in Wide Sargasso Sea). She dominates Rochester through marriage. Madwomen seek power over men, and greater knowledge (tied back to Eve in Eden). Women were linked symbolically with Nature because of their ability to bear children. Sometimes madwomen were associated with water and drowning, though Bertha herself dies by fire.

People are inexplicably drawn to what terrifies them. These fears and anxieties live on today. There are still outsiders, some by choice and others who have none. Criminals deviate. We all struggle with primal urges and desires. Wherever there are rules, there are always rebels. Perhaps that is why we still enjoy horror fiction. That seminar was the highlight of my first semester. I loved it. Hopefully someday I’ll apply some of these themes to horror stories of my own.

Learn something new everyday! Very interesting – thanks, Andrew!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Just in time for Halloween

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well written, my friend. Excellent explanations and analysis. .

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for your insights that explain why we readers sometimes enjoy horror, Andrew. You may like subscribing to an ezine called wordhaus.com I tried being a volunteer editor with the category of horror/suspense (not my first choice which would have been mystery if Emily Wenstrom had set up a section with that genre), but the horror was too horrible for me. Do you know the folktales of “Golem.” They are fascinating. Cannot wait to read your book. Thanks for contacting me after the MVA Write-In.

Hope you follow me too! Beth

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’re welcome, Beth. I will check out wordhaus, and to answer your question I have heard about the Golem. Good luck with everything!

LikeLike

A very good blog post, Andrew. Keep up the good work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great breakdown of Victorian horror concepts! I would love to hear your thoughts on horror in other cultures!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Peregrine Arc and commented:

A concise summary on some Victorian Monster types and archetypes. Recommend it for any horror enthusiast out there.

LikeLike

I found this fascinating, Andrew. Thanks for sharing with me. One very minor thing I noticed (and I double checked a pdf of Jane Eyre online to make sure my memory was correct)–Bertha actually died from falling (or casting herself over) the edge of Thornfield Hall. The fire did bring her up there (or her illness, or both; I guess it’s up to surmise among us literary folk).

Also interesting–when I did a word search find for Bertha Mason, her name is only mentioned five times (directly) in the novel. That’s telling. Fire (or fireplace), in turn, is mentioned 140+ times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love how classic literature, particularly horror, gives us a window into past social values. Nicely written 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike

What a fun class. I’d love to take a course like this, even though I’m a bit of a wimp when it comes to horror movies. Incidentally, MSM is right down the road from Gettysburg where I live. Maybe I should see if it’s still offered.

LikeLiked by 1 person